Botswana is a peaceful, prosperous, stable country with nearly universal access to clean water, education and health care. However, a high rate of income inequality and poverty concentrated in rural areas are blemishes on Botswana’s otherwise superb record of sustained economic growth and social progress. Harsh climatic conditions, limited arable land and a fragile ecosystem make it very challenging to increase the incomes of the rural poor. The challenge is even greater because Botswana’s legal framework governing rangeland provides incentives to privatize and fence communal grazing land through the development of leasehold ranches. This legal structure favors the concentration of ranching on large tracts by wealthier and more powerful people, causing the poorest households to lose access to land, water and veld products on which their livelihoods depend. As a consequence, the remaining accessible communal land is vulnerable to overuse and land degradation.

Botswana’s increasingly prosperous, increasingly urban population puts ever-greater pressure on the country’s natural resources through its growing demand for food, land and fuel. This pressure has resulted in rangeland degradation, soil erosion, loss of grazing habitat, deforestation, overexploitation of wildlife and wood, water pollution, bush fires, and conflicts between people and wildlife. Of particular concern is the country’s forest land, which lacks the protection of a legal framework accompanied by natural resource governance capacity.

Botswana’s regular reviews of its land and natural resources policies and legislation, and its practice of governing through comprehensive six-year plans have kept a focus on land issues and resulted in some of the more progressive land legislation in Sub-Saharan Africa. However, as experience with the country’s legislation accumulates, some gaps have appeared that donors in general and USAID in particular could assist the government in addressing:

The government of Botswana undertakes review of its land and natural resources laws and policies on a regular basis. In 2005, the government noted the need for laws and revisions to existing law that promote more equitable land distribution, address land conflicts and strengthen systems and institutions for land management. The National Development Plan 10 (NDP 10) (2010–2016) notes that progress was made in support of women’s rights in the country, but identifies education and health as areas experiencing change. No progress is identified in the area of protecting and improving women’s rights to land and other natural resources. During the NDP 10 period, land sector programs will focus on providing land for development and improving the productivity of agricultural land. Only one program, which focuses on supporting small-scale farmers, appears to target women and other marginalized groups.

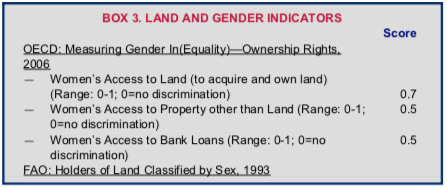

Botswana’s formal legal framework has lagged behind Botswana common law on the support of women’s equal rights to land. For example, the laws governing marriage and marital property contain vestiges of the traditional presumption of male power over family and marital property. Provisions such as those requiring the agreement of both spouses regarding the management of marital property leave room for coercion and abuse. Botswana’s Supreme Court articulated the principle of nondiscrimination in the case of Unity Dow but had to invoke international law for legal foundation. In response to a call from women’s rights activists for a systematic review of legislation to remove discriminatory provisions, the government responded that women have sufficient avenues to raise claims of discrimination. However, such avenues are not accessible to the majority of women, who lack the education, financial resources, knowledge, and assistance necessary to assert their legal rights, especially when the legal grounds are inadequate. In addition, the laws governing grazing land have proved to be inadequate to protect the rights of the small herders, nomadic and semi- nomadic groups, and others relying on access to grazing land for their livelihoods.

The time is ripe for Botswana to revisit its legal framework governing land rights, consider revisions to reflect the principle of gender equality and non-discrimination, and ensure that leasehold grants of large tracts of grazing land do not deprive people of their livelihoods. A revised legal framework can be used to assist the Land Boards in ensuring that women have equal access to land allocations and leasing opportunities. In addition, traditional leaders will have support for reaching nondiscriminatory decisions on the division and inheritance of property, and an enhanced framework will ensure that decisions regarding leasehold grants of grazing land are subject to effective participatory processes and open to challenge.

Botswana has been a trailblazer in the devolution of powers over land-rights management to district-level and sub-district-level Land Boards. However, the process has often left minority groups (e.g., women, those infected with HIV/AIDS, the economically-disadvantaged, ethnic minorities) without power and representation. In addition, in most areas Land Boards have not taken up the responsibility that traditional leaders once had for consulting with their communities and engaging in the overall planning of land-use and management of natural resources. Government and quasi-governmental institutions that are not accountable to local communities are exercising the authority granted to the district Land Boards. Donors, including USAID, can assist the government in its efforts to provide capacity-building and legal literacy campaigns to district and subordinate Land Boards, with the objective of strengthening the decentralized structure and helping local institutions meet their responsibilities to serve all Botswana’s people.

In its report before the Seventh Africa Governance Forum, Botswana expressed the desire to improve its capabilities by enhancing the role of traditional leadership and actively engaging traditional leaders in governance and development processes. USAID has significant experience working at community levels with community-based natural resource management and can use its experience and relationships to assist the government by expanding capacity-building for formal and traditional institutions to include current land and natural resource rights issues.

Botswana has developed a variety of community-based conservation programs primarily focused on wildlife resources but also including some experience with forests and rangeland. USAID has been involved in initiating and helping Botswana execute many of these projects and has substantial experience with community-based natural resource management in other countries. Now may be an appropriate time for USAID to collect experiences and identify lessons learned and best practices. That evaluation could inform the design of larger programs that extend community-based management to larger areas of grazing land and other natural resources, including forest land and water resources that the poorer and most marginalized groups rely on for their livelihoods.

Botswana has enjoyed continuous peace and stability since its independence in 1966. The country ranks as the least corrupt African nation. Ninety percent of the population has access to clean water, education, and health care. Botswana has one of Africa’s highest per capita incomes at US $6470 in 2008, yet also one of the world’s highest rates of income inequality. Forty-seven percent of the population lives below the poverty line, and 97% of all poor people live in rural areas. Twenty-four percent of the population between the ages of 15 and 49 are infected with HIV/AIDS. Average life- expectancy is 38 years.

Botswana is a semi-arid country with harsh climatic conditions and a fragile ecosystem. Arable land is extremely limited, and livestock is the primary source of subsistence and income for two-thirds of rural households. The legal framework governing Botswana’s rangeland incentivizes privatization and fencing of communal grazing land through development of leasehold ranches. These ranches and the benefits of privatization are concentrated in the hands of a few wealthy and powerful people; many of the country’s poorest households have meanwhile lost access to land and natural resources such as water and veld products on which they depend for their livelihoods. The remaining communal land is vulnerable to overuse and degradation.

Botswana’s population is becoming more sedentary and concentrated in its urban areas. Demands for food, land, and fuel are increasing. Threats to natural resources include rangeland degradation, soil erosion, loss of grazing habitat, deforestation, over-exploitation of wildlife and wood, water pollution, bush fires, and conflicts between people and wildlife.

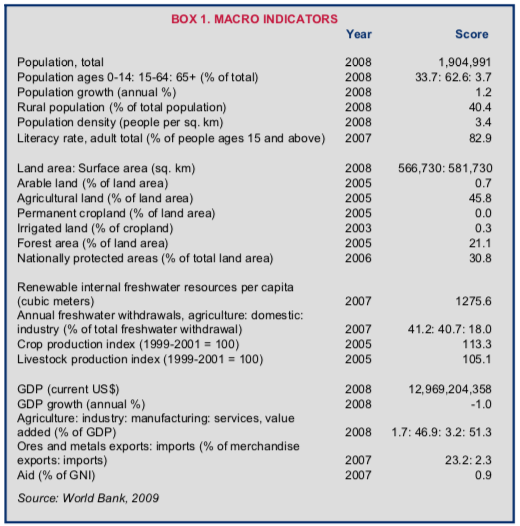

Botswana is a large country with a small population. Botswana has a total land area of 566,700 square kilometers and had a 2008 population of nearly 2 million people, 58% of whom were urban and 42% rural. Eighty percent of the population, settlements, and economic activity are concentrated along a 200-kilometer-wide strip along the country’s eastern border, where the most fertile soil and transportation corridors are located. Botswana’s GDP in 2008 was US $13.0 billion, 47% of which related to industry, 51% to services, and 2% to agriculture. Forty-four percent of the economically active population (57% of which is female) works in agriculture. Per capita income was US $6470 in 2008, but 47% of the population lives below the poverty line (97% in rural areas), and the country has one of the world’s highest rates of income inequality. Twenty-four percent of the population between the ages of 15 and 49 is infected with HIV/AIDS. Average life expectancy is 38 years (World Bank 2009; ROB 2008b; FAO 2005; Anderson 2005; COHRE 2004; PEPFAR 2008).

Most of Botswana is flat, arid land with unreliable, low rainfall. Roughly 46% of the total land area is classified as agricultural land, although only 5% is suitable for cultivation and only 1% was cultivated in 2002. Approximately 0.3% of cropland was irrigated in 2003. The Kalahari Desert, much of which is savanna grassland and sparse woodland, covers two-thirds of the land area and supports large herds of cattle, goats, and wildlife. Twenty-one percent of total land area is forest land and 31% designated as nationally-protected areas. Deforestation is occurring at a rate of 1% per year (World Bank 2009; FAO 2005).

Agriculture includes commercial and traditional farms, with the vast majority of farmers engaged in low- input, rainfed subsistence farming. Commercial enterprises are primarily devoted to the production of cattle, with some cultivation of cereals and pulses. Botswana is unable to produce sufficient food to feed itself and has in some years had to import up to 80% of its food.

Growth of the sector is limited by poor infrastructure and difficult production and market conditions. Only 45% of farmers have access to roads, 22% to telecommunications, 17% to electricity, 64% to water for livestock, 66% to water for domestic use, 39% to grain storage, and 52% to markets (ROB 2010a; Taylor 2007; FAO 2005; Mbendi 2010).

The Tswana (originally belonging to eight separate tribes) are Botswana’s majority ethnic group, making up 40% of the population. Another 37 tribes, constituting 60% of the population, live in the country. The Tswana are among the most educated and wealthiest in the population; the non-Tswana (including the Basarwa or San Bushmen) tend to be less educated and reside in smaller and more remote villages where infrastructure is limited and economic opportunities few. These isolated populations, whose hunting and gathering activities often range over large areas, live in extreme poverty and are highly dependent on access to land and other natural resources for their livelihoods (Adams and Palmer 2007; Adams et al. 2003).

Most of Botswana’s farms (about 63,000) average roughly 5 hectares and are devoted to rainfed farming. The country has about 112 farms larger than 150 hectares. Commercial farms represent less than 1% of all farms in the country and use 8% of the total land area. The enterprises are responsible for 20% of cattle production and 40% of the cereals and pulses produced. Roughly 50% of the large cattle-owners are absentee and have little incentive to manage the rangeland resources sustainably. Most traditional farmers cultivate individually-managed holdings and run livestock on communal land. Their yields tend to be roughly one-third of the yields of commercial farms because they lack the ability to invest in inputs, and because the quality of some of the communal land is below average. The number of landless and land-poor households in Botswana is unknown (ROB 2010a; Taylor 2007; FAO 2005).

Botswana’s government has been criticized for cutting off services to populations of Basarwa in remote areas of the Kalahari Desert and moving them to resettlement camps where services are less expensive. Critics attribute the relocation decisions to the government’s desire to use the land for the development of the tourism and possibly diamond industries; critics identify significant adverse impacts from relocations, including loss of cultural identity, exposure to health hazards, and loss of traditional livelihood skills (Taylor and Mokhawa 2003; ROB 2002).

The legal framework governing Botswana’s land is a mixture of formal and customary laws, with much of the formal law reflecting longstanding principles of customary law. The six major pieces of formal legislation include: (1) The State Land Act, 1966; (2) The Tribal Land Act, 1968; (3) The Tribal Grazing Lands Policy, 1975; (4) The Town and Country Planning Act, 1977; (5) The National Agricultural Development Policy, 1991; and (6) The Sectional Titles Act, 1999 (Adams et al. 2003; Taylor 2007; ROB 2008a; ROB 2010b).

The State Land Act, 1966, provides for management of state land (urban land, parks and forest reserves) by the central government and local government councils, and allocation of urban land to individuals and entities. The Tribal Land Act, 1968 (amended 1993), vests tribal land in the citizens of Botswana and grants administrative power (formerly held by chiefs and headmen) over the land to one of the12 district Land Boards. The Land Boards can allocate land, cancel customary rights, and rezone agricultural land for commercial, residential, and industrial uses. The Tribal Land Act also introduced certificates evidencing grants of rights to wells, borehole drilling, and individual residential plots, and allows people to apply for common-law leases of land, which they use to obtain mortgages (COHRE 2004; Adams et al. 2003; ROB 2008a; Taylor 2007).

The Tribal Grazing Lands Policy, 1975, allows for the privatization of grazing land by vesting the Land Boards with the authority to grant private individuals and entities exclusive leasehold rights to tracts of formerly unfenced, communal land regardless of tribal affiliation. The Town and Country Planning Act, 1977, governs the development of rural and urban land (Adams et al. 2003; Taylor 2007).

The National Agricultural Development Policy, 1991, permits owners of boreholes to apply for 50-year leases to an area of 6400 square hectares around their boreholes. Leaseholders are permitted to fence the area and have exclusive rights to all natural resources within the area. 6) The Sectional Titles Act, 1999, allows for the transfer of rights to sections of developments and properties, such as in condominium and industrial developments, upon approval of a sectional plan for the property. The Sectional Titles Act applies to all types and classifications of land (COHRE 2004; Adams et al. 2003; ROB 2008a; Taylor 2007; ROB 2010b).

Customary law in Botswana provides tribe members with a right of avail, which is the right to be allocated residential (urban or rural), arable, and grazing land based on tribal membership. Tribal members receive land at no cost and have continuing rights to the land so long as they use it in accordance with the purpose of the allocation. Rights to residential land are permanent and continuous, while individually-cultivated land may revert to community land after harvest. Customary law permits the transfer of land among tribe members. The Tribal Land Act is almost wholly consistent with customary law but transfers the traditional authority held by chiefs and headmen over land to the Land Boards (Adams et al. 2003; ROB 2002).

Seventy percent of land in Botswana is tribal land, 25% is state land, and 5% privately-owned freehold land (ROB 2002). The following are the recognized tenure types:

Private ownership. Individuals and entities can obtain private ownership rights to individual parcels of land through land purchase. Most owners obtained freehold rights in colonial times, and the land has either remained in the family through generations or been sold. Most freehold land is located in urban areas although some large cattle ranches (over 100,000 hectares) are freehold land. Ownership rights are held in perpetuity or for 999 years (ROB 2008a; Adams et al. 2003).

Leaseholds. The state leases urban land to individuals and entities under Fixed Period State Grants for 50-year terms for commercial purposes and 99-year terms for residential purposes. At the end of the term, the land and all improvements revert to the state without compensation. Leaseholders can transfer their rights to a third party, subject to the terms of the primary lease. The state has also granted Certificates of Rights to serviced urban plots for the purpose of erecting owner-occupied houses. The owners receive unregistered perpetual occupancy rights. This category of land right is currently suspended (ROB 2008a; Adams et al. 2003).

Customary rights to tribal land. Most land in Botswana is rural tribal land, to which eligible citizens can obtain rights through the Land Board. Citizens can obtain either land grants or leases that allow them to occupy and use allocated parcels of land. The land is heritable but not saleable (Burgess 2002; Adams et al. 2003).

All citizens of Botswana are entitled to receive an allocation of tribal land from the district Land Boards. The 1993 amendment to the Tribal Land Act permits any citizen, regardless of tribal affiliation, to apply for any land, and extends the right to women. Despite the amendment, the Land Boards often continue to assume that women obtain access to land through their husbands and may discriminate against applications for land from women (ROB 2002).

In addition to the tribal land allocations, all citizens are also eligible for two serviced plots in urban areas of the country, whether for residential, commercial, or industrial use. The citizen must develop the first plot before being eligible for the second plot. Citizens must pay for the plots at a price determined by the category of land use, although the state Self-Help Housing Agency (SHHA) assists low-income residents. The SHHA does not, however, extend to the lowest income and no-income groups, and demand for housing assistance far outpaces the funds allocated to the program. Only citizens of Botswana are entitled to land grants under the Tribal Land Act and the State Land Allocation Policy, and the allocated land rights pass through inheritance within families (Adams et al. 2003; ROB 2002; COHRE 2004).

Traditionally there was no squatting on tribal land because tribal land was available to all tribal members at no cost. With migration to urban centers and saturation of available land, the growing population has spilled into surrounding lands and villages. The Land Boards have been unable to meet the demand for plots in peri-urban areas and surrounding communities, and people have erected houses on tribal rangeland. Holders of tribal lands have begun selling plots, contrary to the directives of Land Boards (ROB 2008a).

Citizens and non-citizens can also apply to Land Boards for common-law leases of tribal land, and to lease grazing lands. Under the Tribal Grazing Lands Policy, ranches are standardized at 6400 hectares (8 square kilometers). Foreign individuals and entities can purchase land rights in Botswana, although under Land Control Act, 1975, they must obtain permission from the Ministry of Agriculture to purchase rights to agricultural land (Adams et al. 2003; ROB 2002; Burgess 2002).

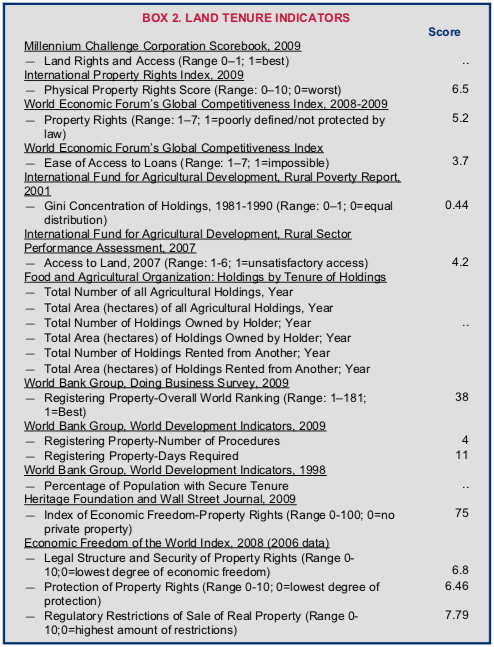

Tenure security in all classifications of land is generally high among Tswana landholders and other tribes with large populations and political power. Freehold land rights are registered with the Registry Office under the Deeds Registry (Amendment) Act, 1996. Assuming continued use of the land, tribal land allocations are perpetual, and lease terms for tribal and state land are standardized. In contrast, the rights of the urban poor, smallholders, and others who are unable to compete with large livestock-owners for grazing land leases are far less secure. Poor migrants to urban areas are increasingly developing informal settlements on the outskirts of cities, and the government has initiated a practice of destroying unauthorized settlements (ROB 2008a; Adams et al. 2003; Taylor 2007; ROB 2002).

In rural areas, smallholders and nomadic tribes have lost access to roughly 8% of communal grazing land. Critics have accused the Land Boards of evicting isolated groups such as the Basarwa from the Central Kalahari Games Reserve and allocating rangeland used by poor stockholders to elite ranchers and foreign interests (Taylor 2007; Ng’Nyati-Ramahobo 2007).

Botswana has a deeds registration system, and pursuant to the provisions of the Deeds Registry Act, 1996, (as amended) deeds evidencing all transactions in private and state land must be recorded at the Registry Office, which is housed within the Attorney General’s Chambers. The Registry’s files generally provide reliable information about property, rights holders, and encumbrances. Compliance with the deeds registration system is high; the only transfers outside the system are customary grants of tribal land and allocations of state land for residential purposes, and in townships and municipalities to poor households under the Self-Help Housing Agency. Registration of land transactions with the Registry Office requires four procedures, takes an average of 11 days, and costs 4.99% of the property value (Ng’ong’ola 1998; World Bank 2008).

The formal law permits women to own land individually and to transfer their land rights without spousal consent. In practice, however, the Registry Office often insists on including the husband’s name on a married woman’s property-registration, and evidence of his consent for transfer (COHRE 2004).

Botswana’s Constitution provides that every citizen is entitled to fundamental rights and freedoms without regard to

gender. The formal law further provides women and men with options to hold land as individuals or, if they are

married, either individually or jointly. The Married Persons Property Act, 1971, allows married couples to choose to marry “in community of property” or “out of community of property.” In the former case, a joint estate is created that contains the couple’s pooled property, and the couple shares profits and losses. Upon divorce, the couple splits their estate. If the couple elects “out of community of property” status, they retain their individual rights to their property acquired before marriage and must enter into an agreement regarding the rights to and management of property gained during marriage. In practice, women may not have any greater rights to control property gained during marriage under the “in community of property” system because in practice the property is almost always registered only under the husband’s name (ROB 1966; COHRE 2004).

Prior to its 1996 amendment, the Deeds Registry Act gave husbands power over any marital property to manage as they saw fit, including transferring the property without wives’ consent. The 1996 amendment to the Deeds Registry Act reined in husbands’ control by providing that both spouses must either be present for any actions affecting the rights to immovable property (e.g., sale, transfer), or provide written consent to the action. The amendment’s impact has been limited because it does not reach moveable property, and the requirement of consent is challenged as easily circumvented (COHRE 2004).

Under the Administration of Estates Act, 1979, if a married couple adopts a “community of property” regime to govern its property, a spouse has the authority to pass half of the marital property at death as he or she wishes, and the surviving spouse retains his or her half. If the couple adopts an “out of community property” regime, property gained during marriage is subject to the agreement of the spouses. In many cases, the property ends up registered in the name of the husband and under his total control, with the wife’s rights unrecognized. The rights of women in unregistered relationships are similarly unprotected. In both cases, the decedents of the male partner often end up with the property (COHRE 2004).

Despite some protective provisions for women in the formal laws, in practice the implementation of the formal laws reflect principles entrenched in Botswana’s customary law. Under customary law, rights to arable land are granted to the head of household, who is usually the household’s eldest male member. Married women are legal minors under customary law and must have their husbands’ consent to buy or sell property, enter into contracts, or apply for credit. The eldest son inherits the family property, with an obligation to care for his mother and unmarried sisters until their marriage. Daughters are only able to inherit property owned individually by their mothers (Adams et al. 2003; COHRE 2004).

Some inroads for equality of women’s rights have been made. In a 2003 High Court case entitled Unity Dow v. Attorney General of Botswana, parties seeking equal treatment of women used Botswana’s ratification of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) in 1995 and the Constitution to support their position that the Citizenship Act unlawfully discriminated against women on the basis of gender. The High Court found the discriminatory provision of the Citizenship Act unconstitutional. In the wake of the court decision, women’s advocates have pressed the government to review and nullify all legislation and government practices contrary to the commitments in CEDAW. The government’s representatives have responded that there is no plan for a systematic gender review of all legislation and government practices, but women can use the Constitution to challenge any discriminatory practice in court, and the government plans other steps to support women’s rights such as campaigns to educate chiefs (CEDAW 2010; COHRE 2004).

The Ministry of Lands and Housing is responsible for the management of land and the delivery of housing throughout the country. The Department of Lands administers state land, regulates freehold land through the Land Control Act, 1975, and provides technical advice on tribal land matters. The Department includes four divisions: Administration; Estates and Land Valuation; Land Inventory and Management; and Land Use and Development. Additional departments within the Ministry of Lands and Housing are the Department of Town and Regional Planning, established to manage urbanization and provide for the efficient utilization of public and private land, and the Settlement Planning Division, which prepares and implements development plans for urban areas and villages (ROB 2008a; Anderson 2005; Adams et al. 2003).

The Land Board derives its authority over tribal land from the Tribal Land Act of 1968. Land Boards grant rights to use tribal land, authorize and transfer tribal land rights, and manage any repossession of tribal land. The Land Boards are required to maintain registries of land grants. The Ministry of Lands oversees the rule-based allocation of both State and Tribal land and is responsible for appointing members of the Land Boards, with input from Land Board staff. Some critics have noted that the relationship between the Land Board members and staff creates potential for lack of adequate supervision of staff, a lack of accountability for staff actions, and the potential for corruption. From time to time, commissions of inquiry, the courts, and the Land Tribunal examine allegations of corruption within the Land Boards. Claimants have alleged that Land Boards have allocated land without following the required procedures for consulting the District Council and neighboring communities, and without advertising the land to give citizens a chance to apply or object (Adams and Palmer 2007; ROB 2008a).

In addition to these formal institutions, and despite the creation of Land Boards, some of Botswana’s chiefs and headmen continue to wield some authority over land matters. In many areas, the Land Boards have not taken up the responsibility (previously held by traditional leaders) for consulting with communities and engaging in the overall planning of land-use and management of natural resources. In some areas, traditional leaders continue to play a role. The nature and scope of the authority varies by region and individual (Adams et al. 2003).

The land market in Botswana is dominated by land transactions relating to private and state land (as opposed to tribal land). Botswana has an active formal market in private freehold land rights, including sales, leases, assignments, and mortgages. Deeds evidencing all transactions of private and state land must be recorded at the Registry Office pursuant to the provisions of the Deeds Registry Act, 1996 (as amended) (Ng’ong’ola 1998).

Tribal land is generally available for allocation by Land Boards, but good-quality land is scarce and efforts to systematically record land information have been slow. Accordingly, records of landholdings are limited. A lease market for allocated tribal land is developing. Land plots in urban centers (both private and state land) are recorded in the State Land Integrated Management System. The plots are increasingly expensive, and state land allocations include requirements for development. If residents are unable to develop allocated plots, the state repossesses them. In 2001, the state had repossessed roughly 13% of the middle- and upper-income area plots allocated, and 55% of plots allocated to low-income residents (Adams et al. 2003; ROB 2002).

Botswana’s relatively nascent land market operations could be assisted by: (1) reducing transaction costs by simplifying procedures and improving the efficiency of Land Boards and the Registry Office; (2) making the records held by the Registry Office a matter of public record and providing transacting parties with more accurate information about land; (3) providing for efficient, low-cost surveying; and (4) reducing risks and uncertainties by clarifying the requirements for legal and enforceable transactions (Adams et al. 2003; ROB 2002).

Article 8 of Botswana’s Constitution provides that the government can acquire property under the following circumstances: (1) in the interests of defense, public safety, public order, public morality, public health, town and country planning or land settlement; (2) in order to secure the development or utilization of property for a beneficial community purpose; and (3) in order to develop or utilize mineral resources. Landholders are entitled to prompt payment of adequate compensation for the land rights acquired, and have a right to seek the judgment of the High Court on the rights held, the legality of the acquisition, the amount of compensation, and payment of compensation (ROB 1966).

The Tribal Lands Act authorizes the Land Boards to acquire, repossess, and rezone tribal land necessary for development. If the state requires tribal land for public purposes, it makes application to the Land Board for reclassification of the land as state land, and a committee of the Land Board determines a rate to compensate the landholder for any improvements made to the land and standing crops. The Acquisition of Property Act authorizes the state to acquire private land for public purposes upon payment of fair compensation. Compensation should account for the value of the land and any improvements, the value of standing crops, the loss of use rights, and costs of resettlement, if necessary (ROB 2008a).

Land disputes over access to urban and peri-urban land, grazing land, and forests are increasing in frequency. For tribal land, Land Boards serve as an initial forum to hear disputes and complaints. The Tribal Land (Establishment of Land Tribunals) Order of 1995 provides for the establishment of tribunals to hear appeals of decisions made by the Land Board. The tribunal is a three-member team chaired by a president who is also a lawyer. The tribunal proceedings are open to the public, and parties may appear with or without separate representation. Parties can appeal the decision of the Land Tribunal to the High Court. The Land Tribunals appear to operate as an effective check on the Land Boards in at least some instances. In well-publicized cases, two Kgalagadi community trusts have successfully used the Land Tribunals to challenge the decisions of Land Boards to lease communal grazing land to foreign-owned companies without consulting with the District Council or advertising the land leases (Adams and Palmer 2007).

There is no separate tribunal dedicated to cases involving private or state urban land, and disputes over the land are increasing. The state is unable to keep up with demand for urban housing, and informal settlements that lack planning, infrastructure, or services are increasing. Parties with disputes must use the formal court system, which has been criticized as often costly, inefficient, and inaccessible to poor litigants (ROB 2002).

The government manages the country with the aid of six-year plans known as National Development Plans (NDPs). In preparing the NDP 10 (2010–2016) land sector strategy, the government identified as its primary concern in the land sector the limited availability of land for development. Barriers to making land available for development include limited private-sector involvement due to lack of basic infrastructure, a shortage of funds for the provision of services to available land, an increase in development costs, encroachment of agricultural land, lengthy land-acquisition processes for freehold land, and land speculation.

The NPD 10 outlines four programs to make land available for development. The first is a land acquisition and allocation program under which the government will purchase freehold land for village expansion and other residential, commercial, and industrial purposes. The government will purchase land on a “willing seller-willing buyer” basis as it becomes available and will not purchase land suitable for agriculture for this program. The government will supply basic services to attract investors and has committed to providing 70,000 new plots with services by 2016. The second program, aimed at land information management, will create a comprehensive land resource database through the computerization of all land records, including those filed with the Land Boards and the Department of Lands Deeds Registry, and the creation of a Physical Planning Portal. The third initiative is a spatial information management program that will produce maps of the entire country and facilitate the surveying of plots. The fourth is a land management program that facilitates the preparation of settlement development plans by local authorities, including demarcation of boundaries between state and customary land and delineation of districts. The program will also generate studies to determine economic rentals for tourism areas, improvement of capacity-building systems, and an integration of land administration procedures and processes (ROB 2010a).

In the agriculture sector, NDP 10 recognizes that the sector is primarily based on traditional communal and subsistence rainfed farming systems with low input. Commercial farming is limited and productivity is low. Barriers to increased productivity include farm fragmentation, inadequate resources, recurring drought, pests and diseases, non-affordability of critical inputs, and low adoption of improved technologies. The country’s objectives in the 2010–2016 period are: to facilitate the growth and competitiveness of the agricultural sector in the economy; enhance farmers’ capability and willingness to use resources in a sustainable manner and ensure prudent use and management of rangeland resources; and provide for human resource needs in agricultural and related sectors. The government plans to develop programs for arable agricultural development to improve small farmers’ production through increased access to technology-transfer and treated wastewater for irrigation and application, livestock development through improved infrastructure and supply of inputs, and agricultural business development, which will focus on supply chains and production standards (USAID/SA 2010).

NDP 10’s Support to Household Food Security and Small, Micro and Medium Size Enterprises Program is aimed at enhancing production levels and sustaining livelihoods for small-scale farmers in rural areas. This program will target women and marginalized groups who engage in small-scale agriculture. The strategy focuses on the provision of subsidized services, inputs, skills and the promotion of clustering through service centers to be distributed strategically across the country (ROB 2010a).

Botswana’s limited overseas development assistance amounts to 0.8% of the country’s gross national income. The United States is the highest contributor, followed by Germany and the European Union. Most partners, notably the Gates Foundation, are focused on the AIDS pandemic. Multilateral development banks own the bulk of the external debt, most of which has targeted infrastructure projects (World Bank 2003).

While USAID closed its Mission in Botswana because the country graduated from U.S. bilateral assistance, USAID continues to provide assistance through its Regional Center for Southern Africa, which is based in Gaborone. USAID has had a significant presence in Botswana, concentrating on assisting the government with issues related to health and human welfare (especially HIV/AIDS) and natural resource management and conservation. USAID provided technical training and assistance in Botswana’s establishment of the Trans-Kalahari Corridor Management Committee, resulting in the execution of an agreement with Namibia and South Africa to enable increased trade in the area (USAID/SA 2010).

The NGO movement is relatively new in Botswana, with most NGOs working in the area of social development and health care. Historically, few NGOs have successfully partnered with local authorities (World Bank 2003).